Delivering the Feature

The Praetorian Fountain in

Palermo.

The Praetorian Fountain in

Palermo.

All stages in the software development lifecycle are important, but some stages are more important than others.

There are many important parts of the software development lifecycle. It's important to understand a business need, otherwise your feature won't be useful. It's important is to devise its requirements, create the designs, split the work and estimate it. Then comes the implementation, testing, delivering it to production and measuring its performance and usage through telemetry.

All stages in the software development lifecycle are important, but some some stages are more important than others. Is it true? Hard to say, maybe it depenends case by case. Are you a startup? A big tech company? Is there a similar product already on the market? There are many aspects to consider when you're prioritising.

We're not going to debate that here. Instead, I would like to advocate the importance of delivering the feature. If it's not being used by costumers, nothing else matters.

The Problem

I was fixing an issue in Microsoft Teams related to a selection inside a search box. After fixing and testing it manually, my next step was to write a unit test using Jest and React Testing Library to make sure the issue won't surface again as a regression. The issue itself is not important, but the test looked, more or less, something like this:

test('should render the search box with the value selected', () => {

const defaultValue = 'good morning'

const {getByRole} = render(<SearchBox defaultValue={defaultValue} />)

const searchBox = getByRole('textbox', {name: 'search for gifs'})

expect(searchBox).toHaveFocus()

expect(searchBox.selectionStart).toEqual(0)

expect(searchBox.selectionEnd).toEqual(defaultValue.length)

})

The test is rendering our search box component, which we expect to be already focused and, if it has default text passed to it, to have it already selected, so the user can overwrite it in one go. The test looks fine, it's easy to understand, it covers the scenario, so we should be all done. In order to take it one step further, I asked myself if jest dom could have a convenience function to test this in one go, and also improve the readability. Something like this:

expect(searchBox).toHaveSelection(defaultValue)

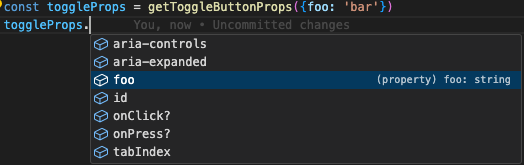

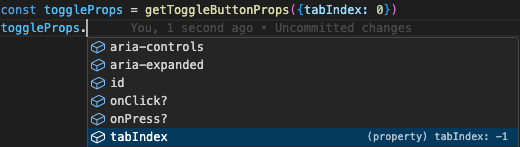

Now, there's nothing wrong with the fist approach, but we can agree that the second one conveys the message better. After checking the functions available in VSCode, and noticing there's no helper expect function, I went to their repo with the thought of submitting a feature request, as I believe it could be a useful addition. Not only did the library already have a feature request, but it also had an open PR to add the function.

The feature request is, at the time of writing this article, almost 4 years old,

and the PR is 3 years old. At first guess, I would expect that the changes

introduced in the PR were not correct, or did not solve the problem one way or

another. However, after checking the discussion and the code itself, the PR was

actually in a very good state. It introduced the correct function, which covered

all the required scenarios. It was able to check both input elements and their

selection, and also random elements that could contain text, from paragraphs to

divs. And for this second use case, the checks were mostly done by using the

range and selection native JS objects, and covered the following:

- whole elemenent was part of the selection.

- the element containing the whole selection.

- element contains part of the selection.

So, why wasn't this PR merged already? There was quite a lot of effort put into

the changes, and users of jest-dom were not reaping the benefits. It made me

curious enough to dive deeper.

The Solution

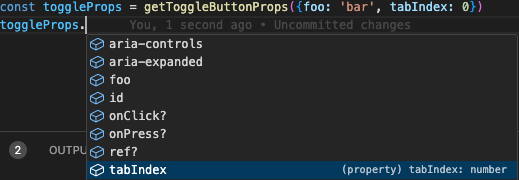

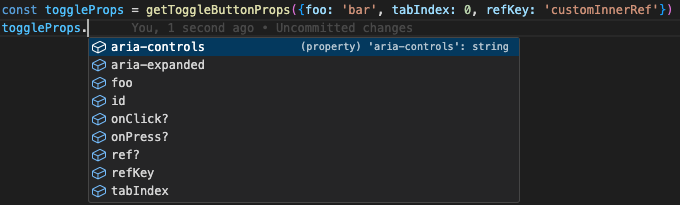

It turned out that the code coverage target of 100% was not met, there was no documentation and no TypeScript support for the changes. Considering all the work that was done until that point, the rest seemed to be a piece of cake. What I did first was to fully understand requirements and the implementation.

We basically need to get the selection for the element we are asserting and

return it. If our element is an input (not a checkout or a radio) or a textarea,

we basically just return the selected text with

element.value.toString().substring(element.selectionStart, element.selectionEnd).

The more challenging part is to get the selection of an element that's not an

input. It could be a paragraph, a div, a span, doesn't matter, it should work in

all cases. For this second case, there are actually 3 scenarios we need to

consider. These scenarios need to account for one action: when user drags a

selection by mouse, trackpad or keyboard (holding Shift). Our function has the

element passed to it, so we get the document selection using

element.ownerDocument.getSelection(). Afterwards, we need to check how much of

that selection is included in element. We have 3 cases.

-

Whole element is inside the selection.

- condition is

selection.containsNode(element, false) - for example, our element is

<span>that's contained in a<p>which got a partial or full selection, including the span. - we get the selection of the element with

selectNodeContents(element)and return it.

- condition is

-

Element contains the selection.

- condition is

element.contains(selection.anchorNode) && element.contains(selection.focusNode) - here we do nothing, since element fully contains

selection, no need to change anything in the initialselection.

- condition is

-

Element contains a partial selection

- this means the selection either starts in the element, or ends in the element.

- you can check in the source code from the link above the API used to get that partial selection that's relevant to the element, based on the 2 cases.

With the selection relative to the element received, we will use the already

established template to build toHaveSelection and it's job done. However, as I

ran the tests, there were a couple of Else branches that were not reached by

the unit tests. I realised that with a bit of refactoring getSelection, it

would be actually easier to test the changes, so I submitted a

slightly different version

for the partial selection condition.

Moreover, even though there was a complete coverage on the tests, I added a few more actions to the test cases, which were missing. 100% test coverage does not mean that you are testig your changes fully. However, less than 100% test coverage means most likely you are not fully testing. Consequently, aim for 100% coverage, but stay skeptical even with that percentage, since it's not a guarantee that your feature is fully tested.

OK, so we've written the tests, we refactored the code, we got full coverage. Since the repo is written in JS, we need to provide separate TS support, but luckily that was easy to do, given the templated previous functions alread written. Finally, I've written a README entry to serve as documentation, and this was actually based on the unit tests, given our function was actually going to be used as a unit test assertion.

Changes done, commited on my forked repo, and submitted a PR to jest-dom, asking the primary maintainer to review. I provided all the context, given the situation, so it would help speed up the process. A few days later, the PR was approved, merged, and included in jest-dom@6.6.0.

The Conclusion

There is a lot of effort which involved so much hard work that is wasted if it's not delivered to your users. We see it all the time, in open source, in a small company that did not finish the product it aimed to deliver, in big tech where there are so many initiatives, hackathon projects and experimental features that do not reach their intended audience. It's probably why I chose to write this article. I want to emphasize that even if your work is not 100% ready to be delivered, that doesn't mean it shouldn't. It's better to aim to finish it 80% feature wise, deliver it and do the 20% later, than implement it 100% and shift focus at 97%. Deliver it at 80%. Hell, maybe even less. Who knows, maybe after reaching the costumers, you may realise that you don't need to do that 20%. Or that the rest of 20% after costumer feedback is now completely different from the initial 20% you initially imagined.

This does not mean that testing, accessibility, telemetry, performance monitoring and all other steps of the software development lifecycle are not important. Far from it. I'm not going to de-emphasize their importance. Just to point out that your effort is only useful when it's used by people, if it makes their life easier or their job less annoying.

Until next time, good luck in delivering great value to the world!

Hilly Landscape in the Village

of Şimon.

Hilly Landscape in the Village

of Şimon. Praia da Arrifana,

Portugal.

Praia da Arrifana,

Portugal. The Morgan Library Museum in New

York. Photo by Silviu Alexandru Avram

The Morgan Library Museum in New

York. Photo by Silviu Alexandru Avram